Lev Goncharov

Infrastructure simplifying engineer

How to test Ansible and don’t go nuts

Date: 2020-05-03

It is the translation of my speech at DevOps-40 2020-03-18:

After the second commit, each code becomes legacy. It happens because the original ideas do not meet actual requirements for the system. It is not a bad or good thing. It is the nature of infrastructure & agreements between people. Refactoring should align requirements & actual state. Let me call it Infrastructure as Code refactoring.

Legacy interception

Day № 1: Patient zero

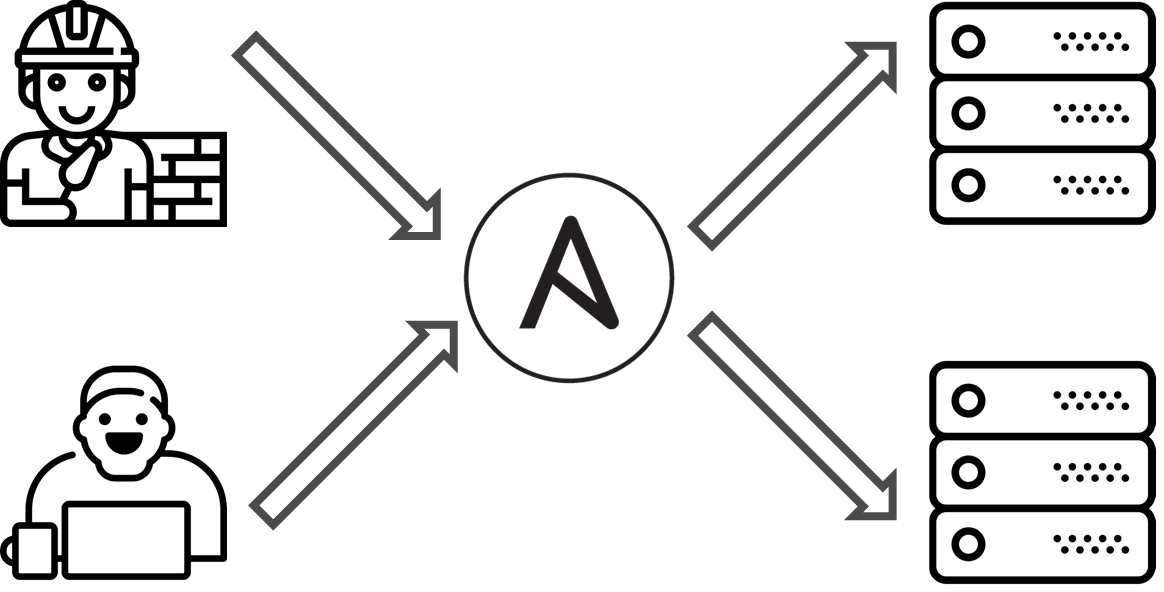

There was a project. It was a casual project, nothing special. There were operations engineers and developers. They were dealing with exactly the same task: how to provision an application. However, there was a problem: each team tried to it do in a unique way. They had decided to deal with it & use Ansible as the source of the truth.

Day № 89: Legacy arise

Time was ticking. They were doing as much as possible. Unfortunately, they got legacy. How did this happen?

- There was a bunch of ASAP tasks.

- It was ok not to write the documentation.

- They didn’t have enough knowledge about Ansible.

- Maybe, there were some Full Stack Overflow Developers - it was ok to copy-paste a solution from the StackOverflow.

- There was lack communication.

The reasons were well known. There was nothing special. It was a standard process. IaC was behaving like code: it was becoming outdatedж it had to be maintained & actualized.

Day № 109: Ok, we have the problem. What’s next?

Original idea / model of IaC became outdated & stuck. IaC did not meet business / customers / users requirements. It became hard to maintain the IaC. They were wasting time struggling with kludges. It was an epiphany moment.

Refactoring IaC

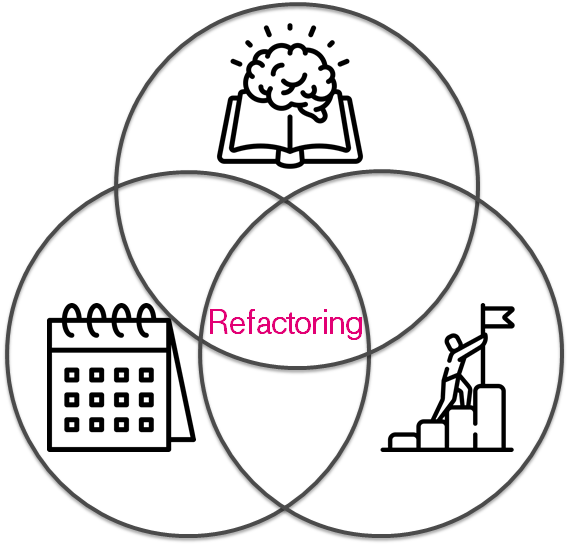

Day № 139: Do you really need IaC refactoring?

First of all before refactoring you must answer three simple questions:

- Do I have a reason?

- Do I have enough time?

- Do I have enough knowledge about it?

If your answers are no, then refactoring might be a problem or a challenge for you. You can do things worse.

In our case, the project knew that our infrastructure team had a pretty good experience in the IaC refactoring (Lessons learned from testing Over 200,000 lines of Infrastructure Code), so our infrastructure team kindly agreed to help with refactoring. It was part of our daily routine to refactor the project.

Day № 149: Prepare to refactor

First of all, we had to determine the goal. We were talking, delve deep into the processes & researching how to deal with the problems. After researches, we made & presented the main concept. The main idea was to split infrastructure code into small parts and deal with each part separately. It allowed us to cover by tests each piece of the infrastructure and understood the functionality of that piece of infrastructure. As a result, we were able to refactor infrastructure little by little without breaking the agreements.

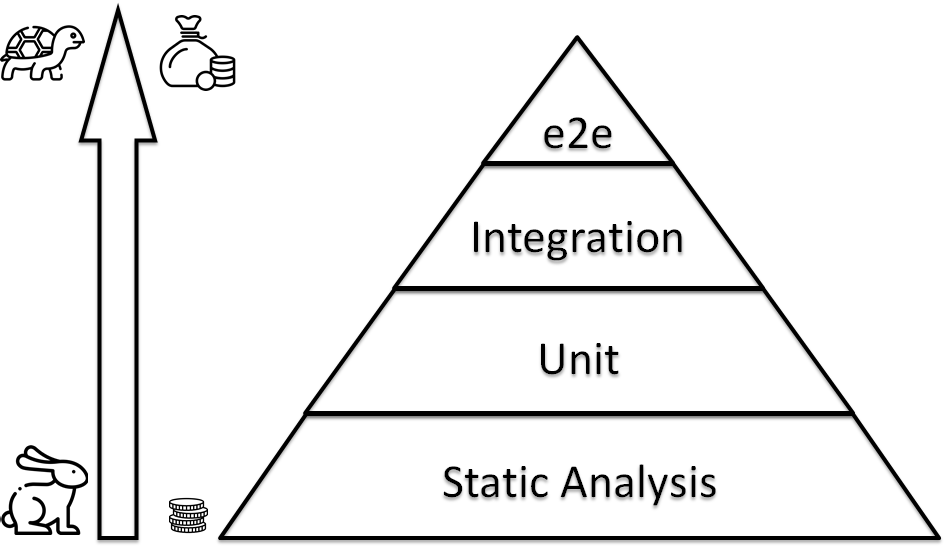

Let me mention about the IaC testing pyramid. If we are talking that Infrastructure is Code, then we should reuse practices from development for infrastructure, i.e. unit testing, pair DevOpsing, code review.. etc.. One of these approaches is a software testing & using testing pyramid for that. My idea is:

- static - shellcheck/ansible lint

- unit - molecule/kitchen + testinfra/inspec for basic blocks: modules, roles, etc

- integration - check whole server configuration - group of roles. again molecule/kitchen

- e2e(end to end) - check that group of servers work correctly as an infrastructure

How to test Ansible?

Before the other part of the story let me share my attempts to test Ansible before that project. It is important because I want to share the context.

Day № -997: SDS provision

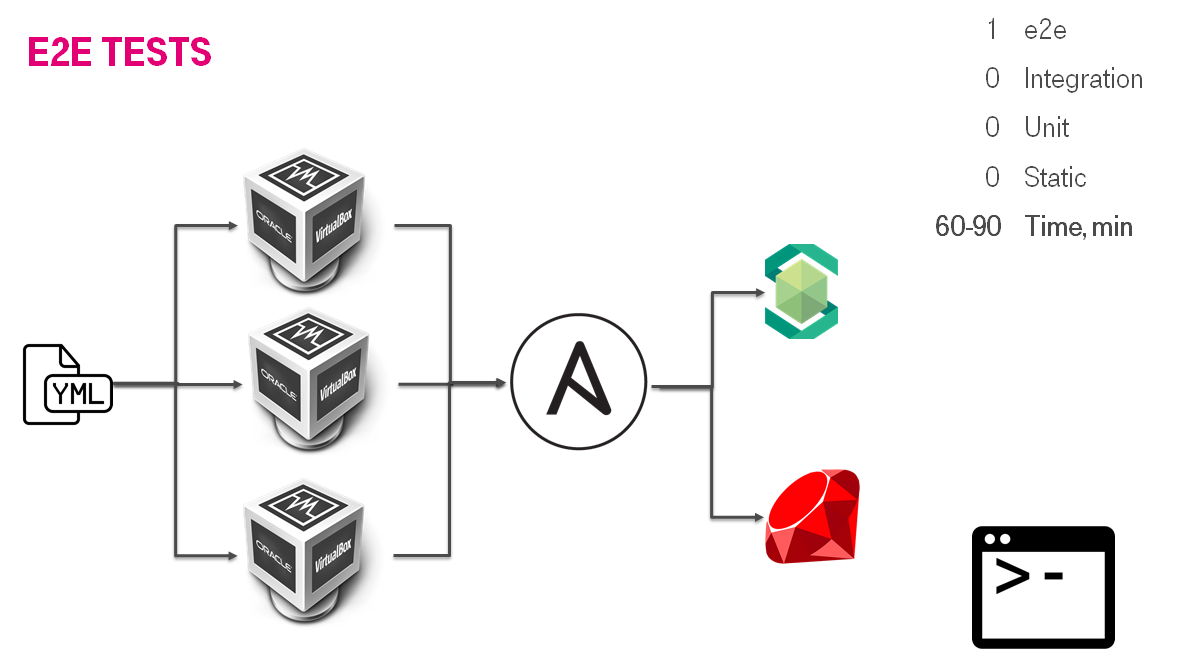

It was a couple of projects before. We were developing SDS (Software Defined Storage). That was software and hardware appliance. The appliance consisted of custom OS distributive, upscale servers, a lot of business logic. As part of SDS, we had a bunch of processes i.e. how to provision the SDS installation. For provisioning we used Ansible. To make a short story long: we had reverted IaC testing pyramid. We had an e2e test and they lasted 60-90 minutes. It was too slow. The main idea was to create the installation & emulate an user activity(i.e. mount iSCSI & write something). We created the IaC testing solution.

You can read a bit more: How to test your own OS distribution.

Day № -701: Ansible & test kitchen

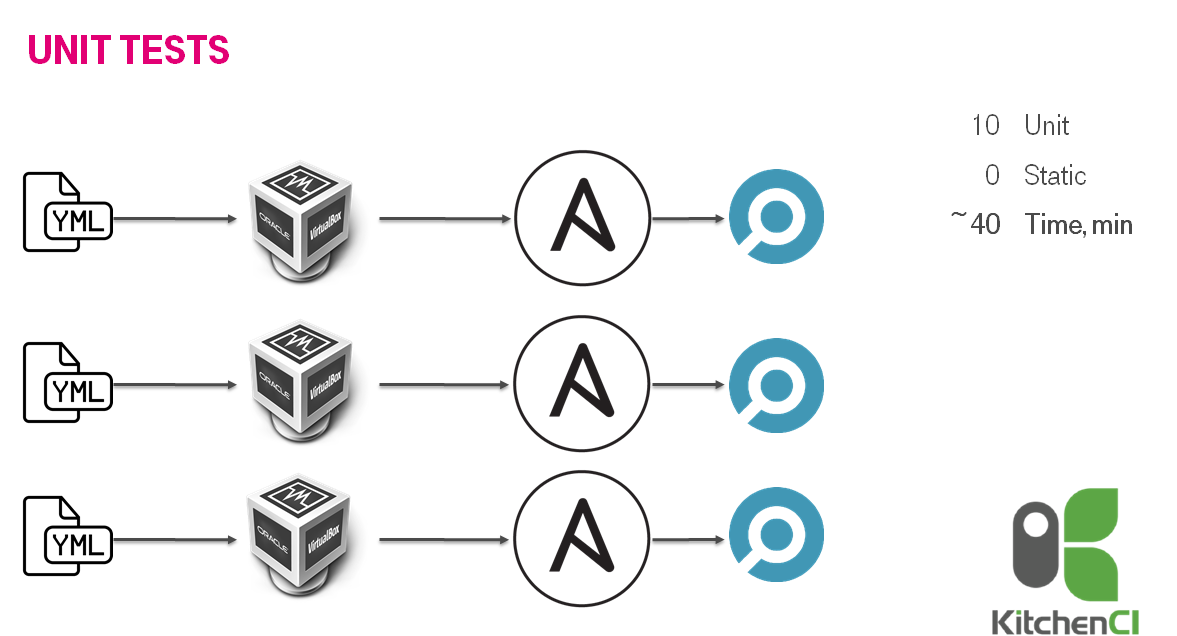

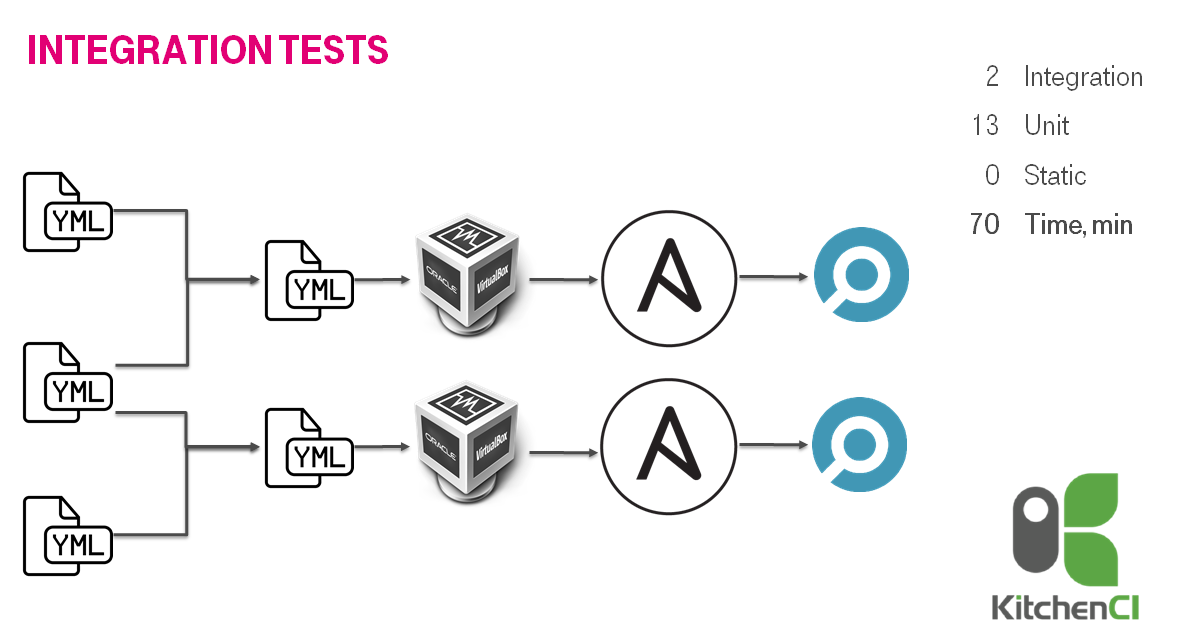

The next idea was not to reinvent the wheel & use production-ready solution, i.e. test kitchen / kitchen-ci & inspec. We decided to use it because we had enough expertise in the Ruby world. We were creating VMs inside a VM. It was working more or less fine: 40 minutes for 10 roles.

You can read a bit more: Test me if you can. Do YML developers Dream of testing ansible?.

In general, it was a stable solution. However, when we increased the number of tested roles to 15(13 base roles + 2 meta roles) we faced an issue. The speed of tests felt down dramatically to 70 minutes. It was too slow. We were not able to think about XP (extreme programming) practices.

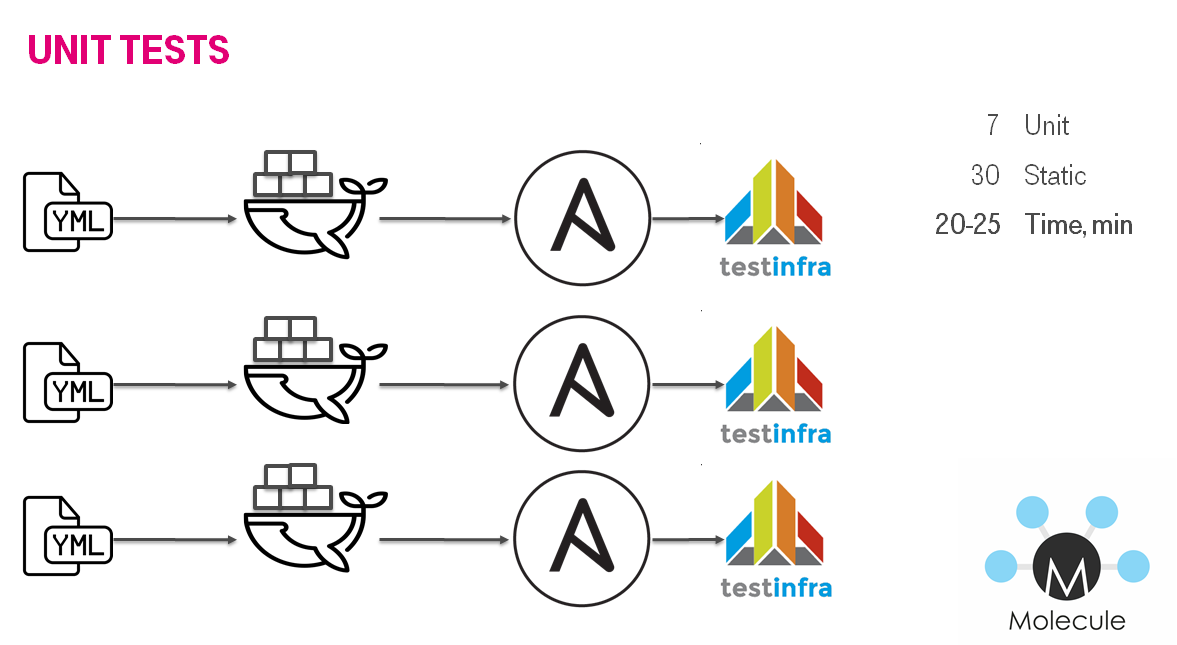

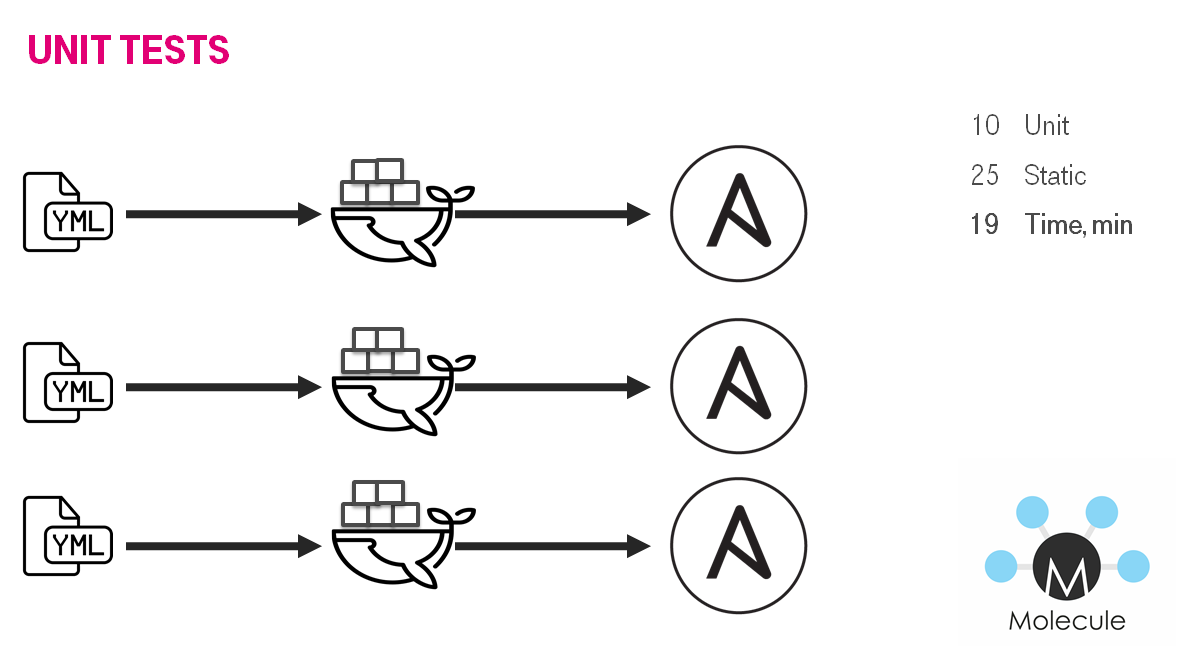

Day № -601: Ansible & molecule

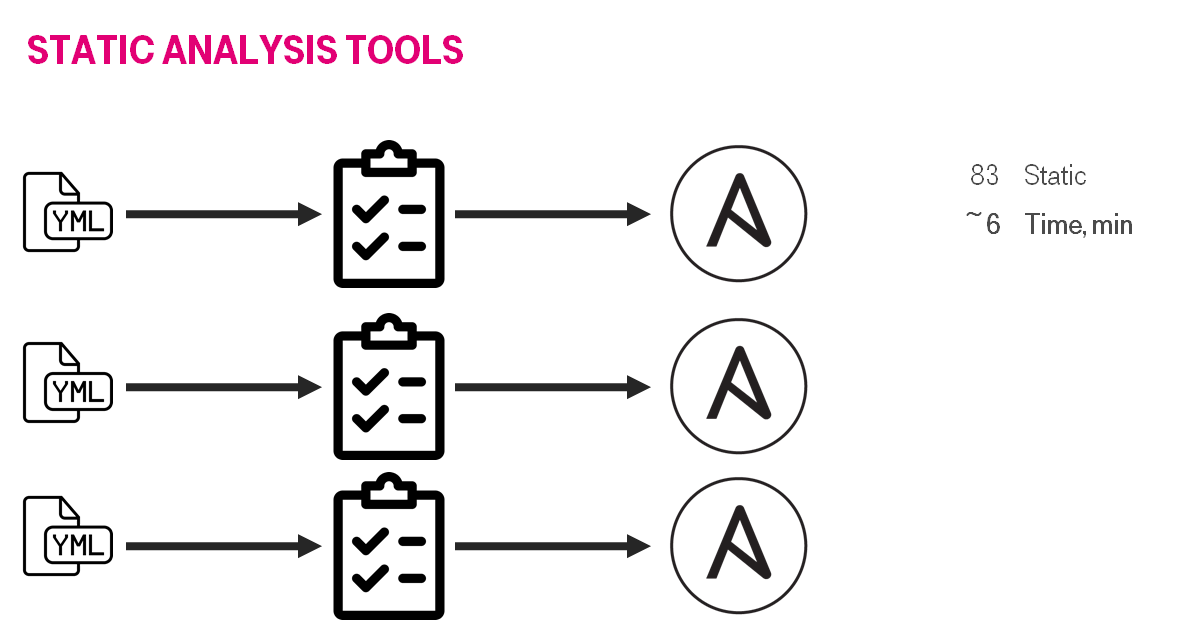

It triggered us to use molecule & docker. As a result, we had 20-25 minutes for 7 roles.

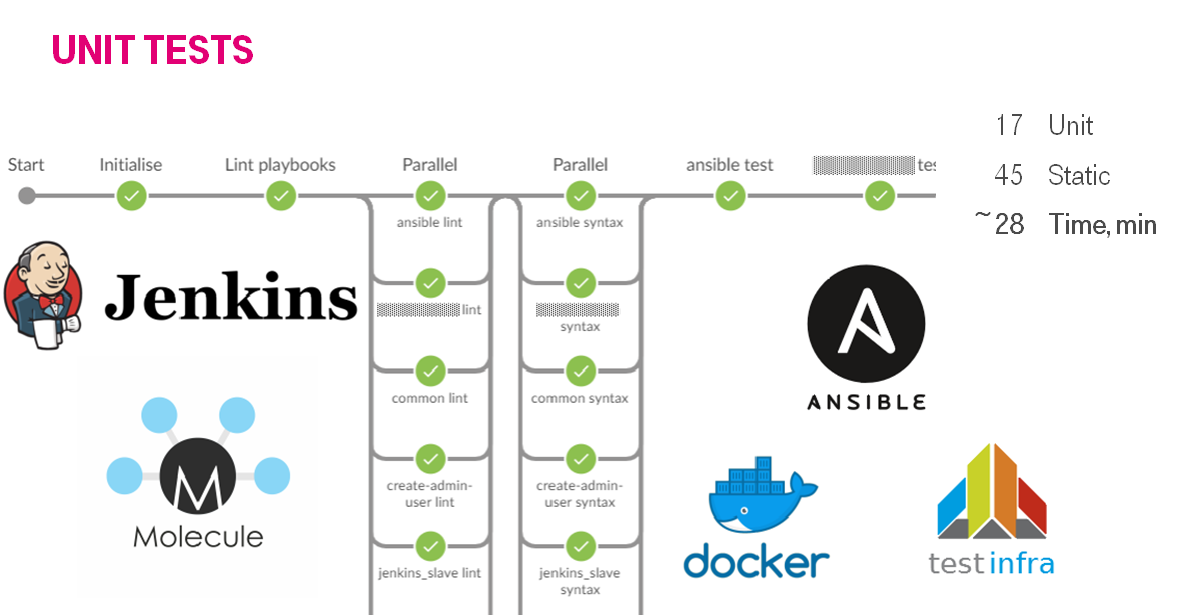

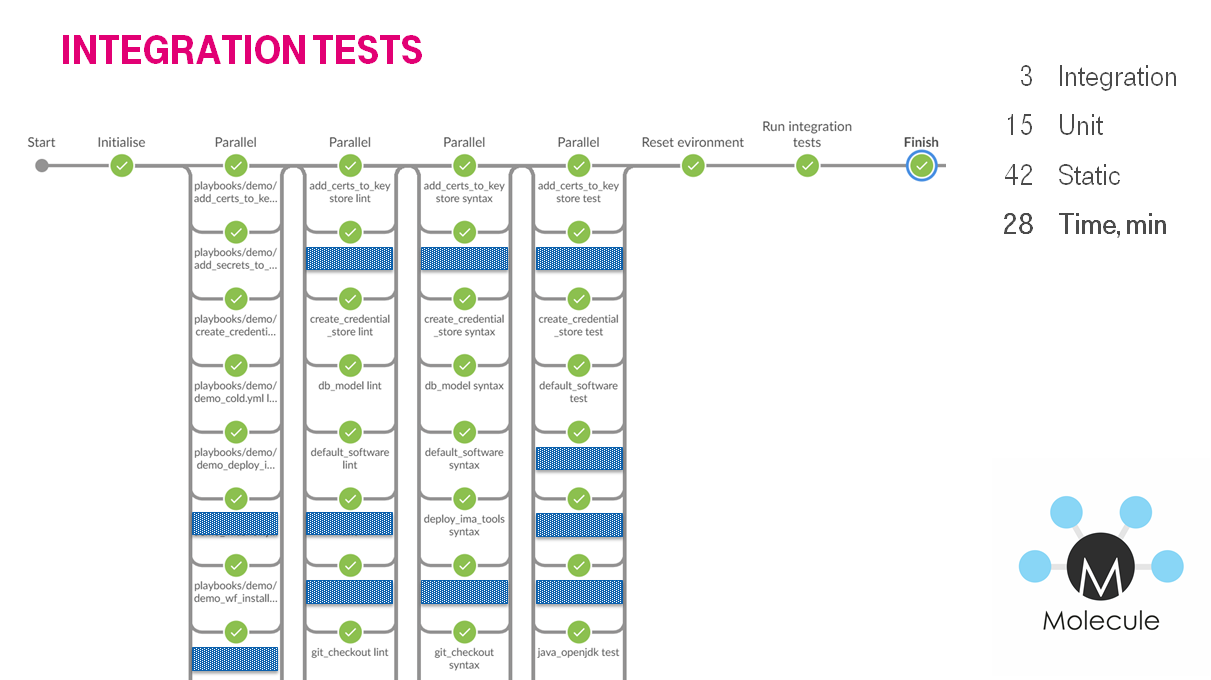

We increased the number of tested roles to 17 & linted playbooks to 45. It lasted about 28 minutes with 2 Jenkins slaves.

Day № 167: Introduce tests to the project

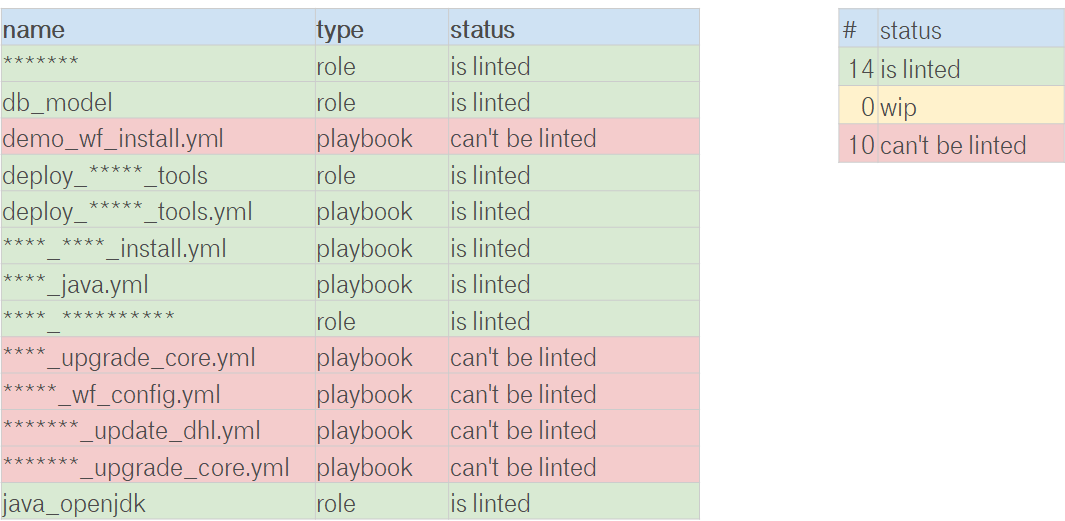

It was a bad idea to test all roles from the very beginning, because it was an immense change. We wanted to change the project little by little and avoid problems. So, we arranged the S.M.A.R.T. goal lint all roles. We were enabling linting roles/playbooks one by one. It was yak shaving: we were slowly improving the project and creating the culture.

It is not really important how to shave the yak. It might be stickers on the wardrobe, tasks in the Jira or spreadsheet in the google docs. The main idea is to track current status & understand how it is going. You should not burn out during refactoring, because it is a long boring journey.

Refactoring is easy as pie:

- Eat.

- Sleep.

- Code.

- IaC test.

- Repeat…

So we started from the linting. It was a good starting point.

Day № 181: Green Build Master

Linting was the very first step to the Green Build Master. It cost almost nothing, but it created good habits & processes inside the team:

- Red test is bad, you should fix it.

- If you see code smell - improve it.

- Code must be better after your changes.

Day № 193: Linting -> Unit tests

We had processes for changing the master branch. The next step was to replace linting via real roles applying. We had to understand how roles were implemented and why.

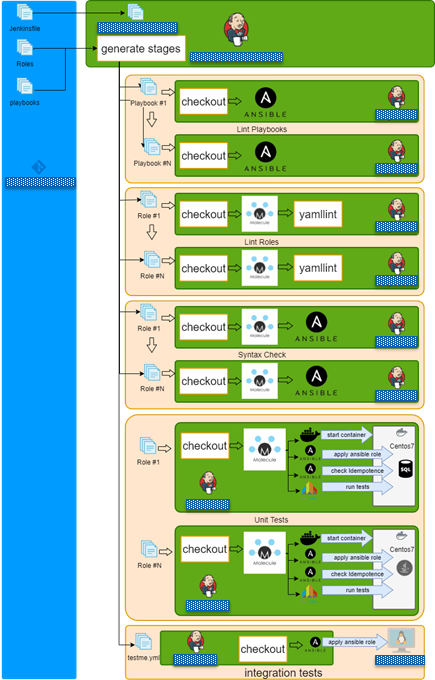

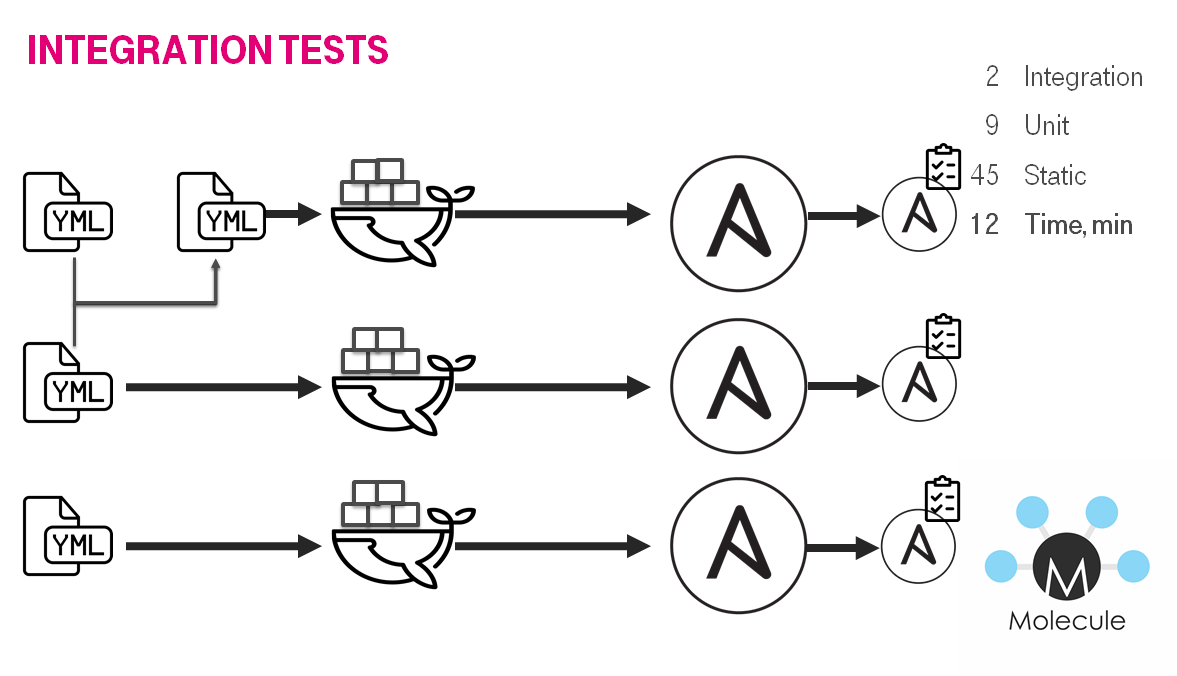

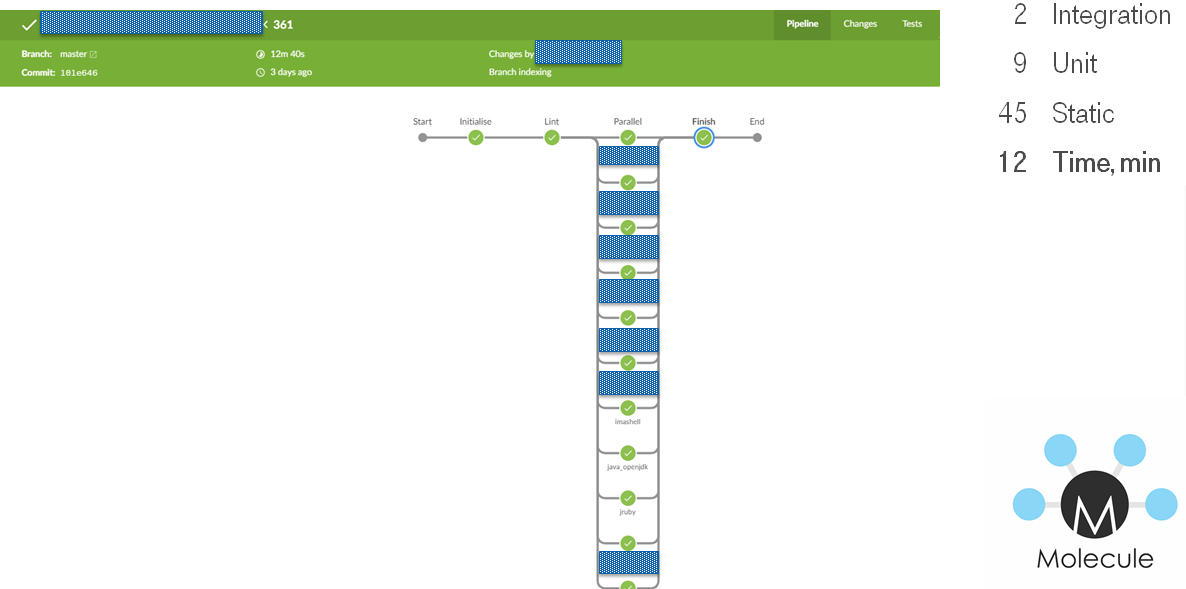

Day № 211: Unit tests -> Integration tests

We finished with unit tests. The vast majority of roles were tested after each commit. The next step was the integration tests. We had to test the combination of simple bricks which created the building - whole server configuration.

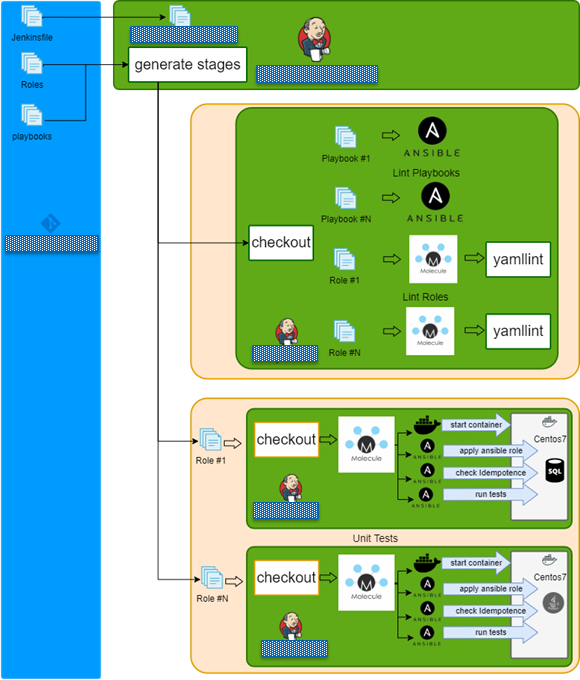

We were generating bunch of stages. The stages were executing simultaneously. Let’s take a look onto this pipeline.

Jenkins + Docker + Ansible = Tests

- Checkout repo and generate build stages.

- Run lint playbook stages in parallel.

- Run lint role stages in parallel.

- Run syntax check role stages in parallel.

- Run test role stages in parallel.

- Lint role.

- Check dependency on other roles.

- Check syntax.

- Create docker instance

- Run

molecule/default/playbook.yml. - Check idempotency.

- Run integration tests.

- Finish.

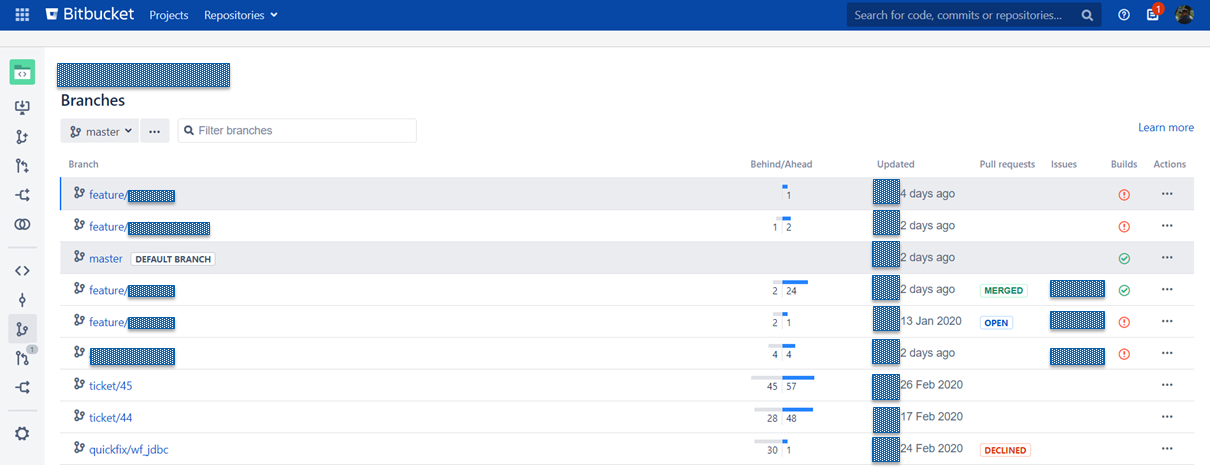

Day № 271: Bus Factor

At the beginning of the project, there was a small amount of people. They were reviewers. Time was ticking and knowledge on how to write ansible roles were spread across all teams members. The interesting thing was that we were rotating reviewers on a 2 weeks basis.

The review process had to be simple & reviewer friendly. So, we integrated Jenkins + bitbucket + Jira for that. Unfortunately, the review is not a silver bullet. i.e. we missed bad code to the master and had flapped unstable tests.

- get_url:

url: "/"

dest: "/"

username: ""

password: ""

with_subelements:

- ""

- ""

delegate_to: localhost

- copy:

src: "/"

dest: ""

with_subelements:

- ""

- ""

Fortunately, we fixed that:

get_url:

url: "/"

dest: "/"

username: ""

password: ""

loop_control:

loop_var: actk_item

with_items: ""

delegate_to: localhost

- copy:

src: "/"

dest: ""

loop_control:

loop_var: actk_item

with_items: ""

Day № 311: Speed up tests

The amount of tests was increasing. The project was growing. As a result, in the worst case our tests were executing for 60 minutes. To deal with that we decided to remove integration tests via VMs & use just the docker. Also, we replaced testinfra via Ansible verifier for unifying toolset.

We made some changes:

- Migrated to the docker.

- Removed duplicated tests & simplified dependencies.

- Increased amount of Jenkins slaves.

- Changed test execution order.

- Added ability lint all roles & playbooks via a single command. It helped to lint all locally via the same command.

As a result, of those changes, the Jenkins pipeline also was changed:

- Generate build stages.

- Lint all in parallel.

- Run test role stages in parallel.

- Finish.

Lessons learned

Let me share some lessons learned

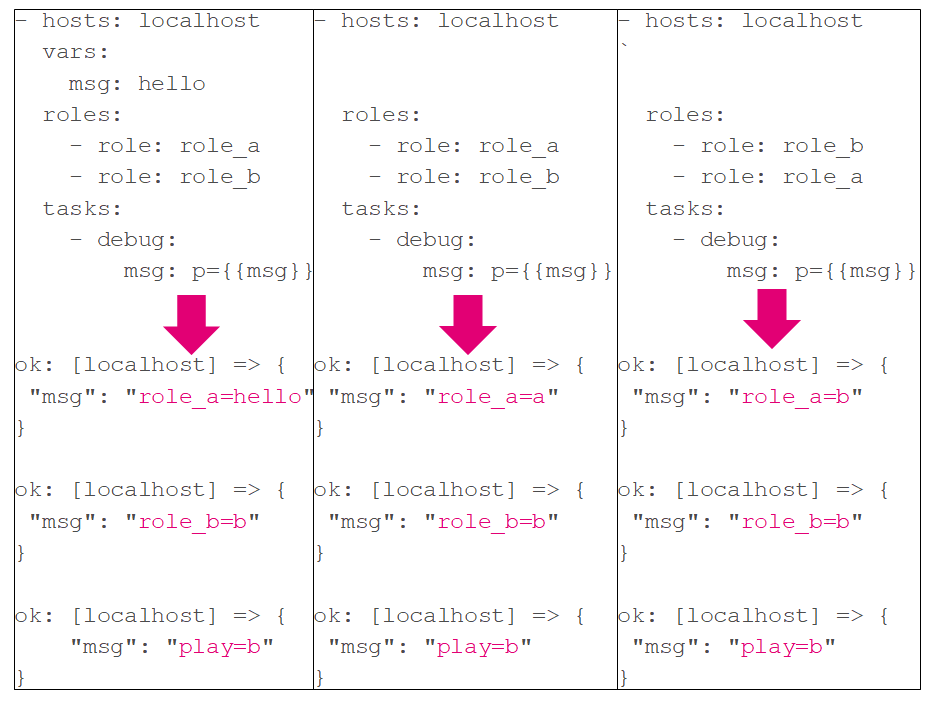

Avoid global variables

Ansible uses the global variable namespace. I know about a workaround via private_role_vars, but it is not a silver bullet.

Let us create two roles role_a & role_b

# cat role_a/defaults/main.yml

---

msg: a

# cat role_a/tasks/main.yml

---

- debug:

msg: role_a=

# cat role_b/defaults/main.yml

---

msg: b

# cat role_b/tasks/main.yml

---

- set_fact:

msg: b

- debug:

msg: role_b=

- hosts: localhost

vars:

msg: hello

roles:

- role: role_a

- role: role_b

tasks:

- debug:

msg: play=

We often need some variables to be accessible globally and shared between different roles. One obvious example is JAVA_HOME. Ansible has a flat namespace, and this can lead to variable names collisions. For example, two roles (say, webserver and mailserver) may use the same variable named ‘port’; such a variable may be accidentally overwritten with the same value in both roles. It’s better to prefix variable names in your roles either by a role name, or some short form of it.

BAD: use a global variable.

# cat roles/some_role/tasks/main.yml

---

debug:

var: java_home

GOOD: In this case, it’s a good idea to define such a variable in the inventory, and use a local variable in your role with a default value of the global one. This way the roles are kind of self-contained, and it’s easy to see what variables the role uses just by looking into the defaults.

# cat roles/some_role/defaults/main.yml

---

r__java_home:

""

# cat roles/some_role/tasks/main.yml

---

debug:

var: r__java_home

Prefix role variables

It makes sense to use the role name as the prefix for a variable. It helps to understand the source inventory easier.

BAD: use a global variable.

# cat roles/some_role/defaults/main.yml

---

db_port: 5432

GOOD: Prefix variable.

# cat roles/some_role/defaults/main.yml

---

some_role__db_port: 5432

Use the loop control variable

BAD: If you use standard item and somebody decides to loop your role you can face unpredictable issues.

---

- hosts: localhost

tasks:

- debug:

msg: ""

loop:

- item1

- item2

GOOD: Override the default variable via loop_var.

---

- hosts: localhost

tasks:

- debug:

msg: ""

loop:

- item1

- item2

loop_control:

loop_var: item_name

Check input variables

If your role requires input roles it makes sense to raise when they are not presented.

GOOD: Check variables.

- name: "Verify that required string variables are defined"

assert:

that: ahs_var is defined and ahs_var | length > 0 and ahs_var != None

fail_msg: " needs to be set for the role to work "

success_msg: "Required variables is defined"

loop_control:

loop_var: ahs_var

with_items:

- ahs_item1

- ahs_item2

- ahs_item3

Avoid hashes dictionaries. Use a flat structure

While dictionaries may seem like a good fit for your variables, you should minimize their usage due to the following:

- It’s not possible for a user to change only one element of a dictionary.

- Dictionary elements cannot take values from other elements. Example: A dictionary that stores some OS user.

BAD: Use hash/dictionary.

---

user:

name: admin

group: admin

Downside: you cannot set the default group name to the user name; if a person using your role wants to customize only the name, they must also supply the group. With regular variables, those issues are gone: Both variables can be changed independently, and the default group name matches the user name.

GOOD: Use flatten structure & prefix variable.

---

user_name: admin

user_group: ""

Create idempotent playbooks & roles

Roles and playbooks have to be idempotent. It decreases your fear to run a role. As a result, configuration drift is as minimum as possible.

Avoid using command or shell modules

Imperative approach via command / shell modules is againsts the declarative ansible nature.

Test your roles via molecule

The molecule is pretty flexible. Let me show some examples:

Molecule Multiple instances

In the molecule.yml in the platforms section you can describe a bunch of instances:

---

driver:

name: docker

platforms:

- name: postgresql-instance

hostname: postgresql-instance

image: registry.example.com/postgres10:latest

pre_build_image: true

override_command: false

network_mode: host

- name: app-instance

hostname: app-instance

pre_build_image: true

image: registry.example.com/docker_centos_ansible_tests

network_mode: host

After that you can use the instances in the converge.yml:

---

- name: Converge all

hosts: all

vars:

ansible_user: root

roles:

- role: some_role

- name: Converge db

hosts: db-instance

roles:

- role: some_db_role

- name: Converge app

hosts: app-instance

roles:

- role: some_app_role

Ansible verifier

Molecule allows you to use ansible verifier instead of inspec / testinfra / serverspec. It’s the default from the 3.0 version.

You can check that file contains expected body:

---

- name: Verify

hosts: all

tasks:

- name: copy config

copy:

src: expected_standalone.conf

dest: /root/wildfly/bin/standalone.conf

mode: "0644"

owner: root

group: root

register: config_copy_result

- name: Certify that standalone.conf changed

assert:

that: not config_copy_result.changed

Or you can start the service & perform a smoke test:

---

- name: Verify

hosts: solr

tasks:

- command: /blah/solr/bin/solr start -s /solr_home -p 8983 -force

- uri:

url: http://127.0.0.1:8983/solr

method: GET

status_code: 200

register: uri_result

until: uri_result is not failed

retries: 12

delay: 10

- name: Post documents to solr

command: /blah/solr/bin/post -c master /exampledocs/books.csv

Put complex logic into modules & plugins

Ansible nature is a declarative approach & YAML. It is extremely hard to use standard developers patterns because there is no syntax sugar for that. If you want to implement complex logic (not straight) in a playbook it will usually be ugly. Fortunately, you can customize ansible via creating your own modules & plugins.

Summarize Tips & Tricks

- Avoid global variables.

- Prefix role variables.

- Use the loop control variable.

- Check input variables.

- Avoid hashes dictionaries. Use a flat structure.

- Create idempotent playbooks & roles.

- Avoid using command shell modules.

- Test your roles via molecule.

- Put complex logic into modules & plugins.

Conclusion

One does not simply refactor agreements & infrastructure. It is a long interesting journey.

P.S.

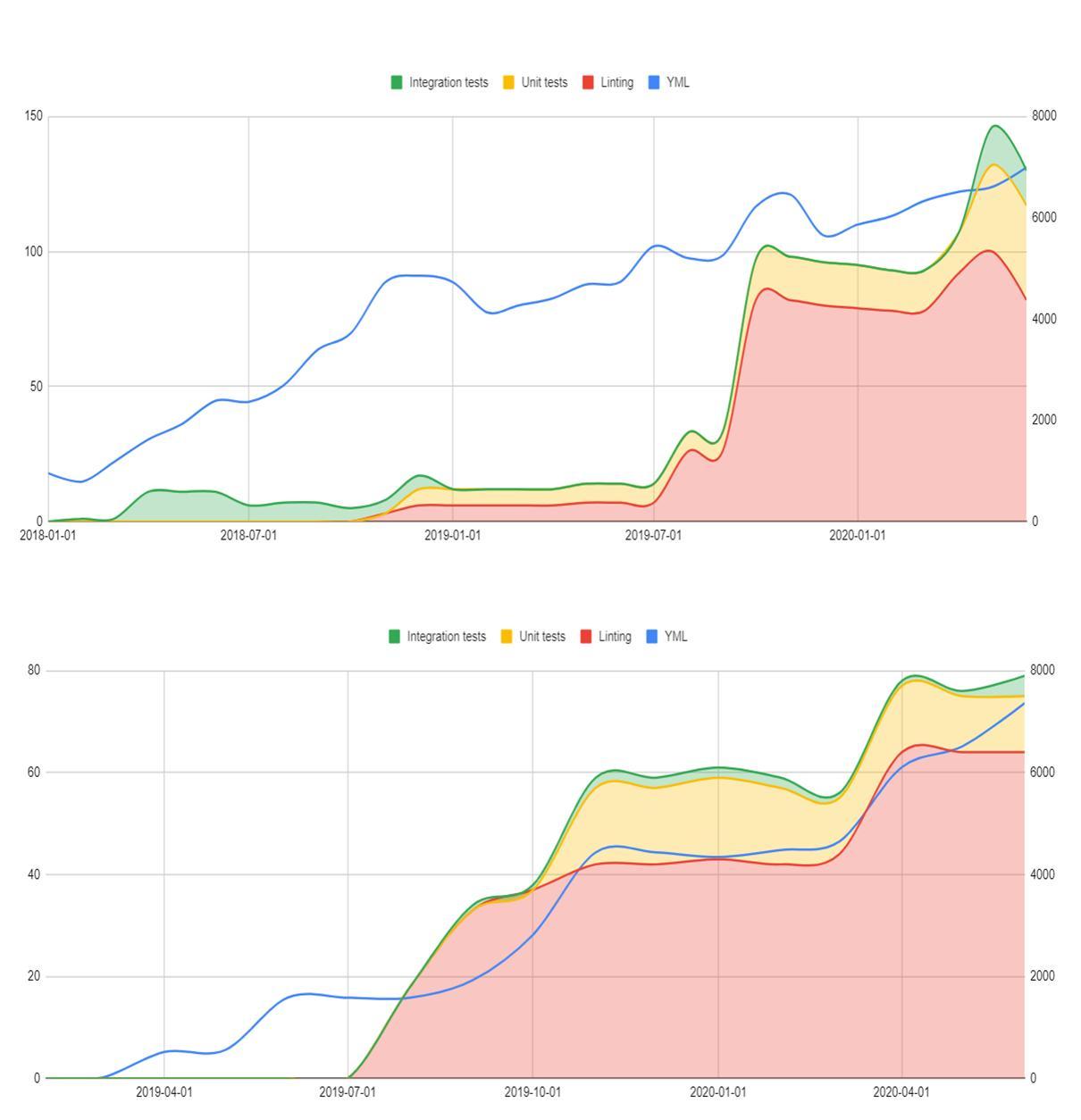

Let me clarify about the plot.

- Ansible tests = amount of tested roles/playbooks.

- SLOC = Source Lines Of Code in YAML files.

Lessons learned:

- Start linting from the very beginning.

- If there are 2000 SLOC and you don’t run molecule you will have problems.

- After 6000 SLOC you should implement e2e tests.

Links

- Cross post

- Slides How to test Ansible and don’t go nuts

- Video How to test Ansible and don’t go nuts

- Lessons learned from testing Over 200,000 lines of Infrastructure Code

- How to test your own OS distribution

- Test me if you can. Do YML developers Dream of testing ansible?

- Ansible: Coreos to centos, 18 months long journey

- A list of awesome IaC testing articles, speeches & links